Copyright © 2007 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 53, No 4 - Winter 2007

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2007 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 53, No 4 - Winter 2007 Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas |

VILNIUS ON THE MAP OF SARMATIA: I

Laimonas Briedis

LAIMONAS BRIEDIS is a native of Vilnius, but was educated in Canada. PhD in Geography in 2005, University of British Columbia. Currently, postdoctoral fellow at the University of Toronto, History Department. His first book Vilnius: City of Strangers is due to be published in winter of 2008 by Baltos Lankos, Vilnius. He lives between Vancouver and Vilnius.

Whoever pronounces the word center implies another word, periphery, and a relationship between the two, either centrifugal or centripetal. Also, a center implies crossing lines, vertical and horizontal. These few elementary notions about space should be present in our mind when we deal with the geography and history of Europe taken as a whole, and particularly of socalled Eastern Europe. Perhaps coming from an area which for a long time has been considered the Eastern marches of Romecentered Christendom makes one more sensitive to shifting points of gravity, symbolized by the very fluidity of such terms as the West and the East.

Czesław Miłosz

The metaphor and name of Europe has its origins in ancient Greek mythology, but the idea of Europe as a geographical unit places its origins in the visualization of the Christian realm of the Renaissance period.1 In the sixteenth century, the name of Europe began to appear regularly on the title pages of various maps and atlas collections. At the same time, through various artistic representations of Greek myths, the idea and representational character of Europe also entered the aesthetic and cultural terrain of the period. John Hale, in his elegant study of Renaissance Europe, described this parallel evolution of cartographical imagination and aesthetic practices as an intellectual passage: “From myth and map, chorography, history and survey, Europe passed into the mind.”2

By the 1600s, the symbolic meaning of Europe became inseparable from its geographical body. Surrounded and safeguarded by water on three sides, Europe gradually dissolved into the vast landmass of Asia. In general, early maps of Europe did not show bias towards the western parts of the continent. The maps, according to Hale, devoid of “indications of political frontiers … were not devised to be read politically. And the busily even spread of town names did not suggest that western [Europe] had any greater weight of economic vitality than eastern Europe. This even-handed appearance of uniformity owed something to the cartographer’s horror vacui, but more to their places of work and the networks of correspondents [...] radiating from them.”3 Most maps were produced in the northwestern parts of Europe with intense commercial, religious, and political connections with the Baltic Sea region. As a result of these networks, neither “cartographers nor traders thought of Europe as comprising an ‘advanced’ Mediterranean and a ‘backward’ Baltic, or a politically and economically sophisticated Atlantic West and a marginally relevant East.” 4

Vilnius, the capital city of one of the largest political entities in Europe, was recognized as geographically equal to any important urban center of western and southern Europe. The city’s cartographic visibility was also sharpened by the relative representational emptiness of its hinterland. There were fewer towns in Lithuania than in other parts of Europe, and except for vast forests and swamps, there were no other significant topographical elements – mountains, large rivers or lakes, etc. – to be mapped out. Indeed, the cartographers of the early Renaissance often exaggerated the topographical features of Lithuania. The rolling, undulating landscape around the city was portrayed in a similar fashion to the mountainous regions of the Carpathians, swampy areas of the Lithuanian-Byelorussian lowlands frequently appeared as immense lakes equal in size to uncharted seas, and minor rivers were delineated as gargantuan waterways.5

Vilnius’s magnified presence was also directly linked to the political conception of Lithuania as a geographical frontier of European civilization. In (western) Europe, the dynastically unified state of Poland-Lithuania became widely recognized as “a steadfast fortress … against the Turks and Crimean Tatars … [and] against those other westward-pressing ‘barbarians’, the peoples of Russia, from the Muscovite heartlands around the capital to the semi-independent Cossacks of the South.”6 This habitual location of Lithuania stimulated not only the Western European geographical imagination (which populated the country with exotic natural phenomena, strange peoples and bizarre local history), but also contributed to “the production of such masterpieces of devoted cartography as Mikolaj Radziwill’s Duchy of Lithuania of 1613.”7 The detailed map, commissioned by Mykolas Radvila (Mikołaj Radziwiłł), a cosmopolitan scion of one of the wealthiest families of the Lithuanian nobility, depicted the vast region stretching from the shores of the Baltic Sea to the central areas of Ukraine. The map ushered the Renaissance practice of accurate cartographical workmanship into the aesthetically mannered era of Baroque rationalism. It became a model of precision and stylistic refinement for generations of European mapmakers. On this map, Vilnius (or Vilna, as it appears on the map) takes center stage not only because of its representational prominence within the hierarchical system of cartographical legend as the main city of Lithuania, but also because the geographical spread of the covered region seems to be consciously centered around the city.

The earliest known map of Vilnius was made in 1513 on a chart entitled Tabula moderna Sarmatia, exactly one hundred years before the appearance of Radvila’s map.8 According to the cartographic legend of the map, this modernized chart of Sarmatia was a revised replica of an earlier map of Sarmatia made by a cardinal and governor of Rome, Nicolus Cusanus (1401-1464), which was printed in Strasburg in 1491 with the title of Sarmatia terra in Europa. Both maps of Sarmatia were published as updates of the classical work of Ptolemy’s Geographia.

|

| Map of Central Europe from Sebastian

Münster’s “Cosmographia Universalis,” Basel 1552. This map shows the area of Sarmatia and Littaw (Lithuania) as well as Vilna (Vilnius) and the river Nemel (Nemunas). See the article “Vilnius on the Map of Sarmatia: I” on p. 23. |

Ptolemy’s original map of Sarmatia specified only natural and ancient ethnographic features of the region – it delineated rivers, seas, mountains and local barbarian tribes. In contrast, Cusanus’s version clearly outlined contemporary contours of Sarmatia by mapping out the recognizable countries of Hungary, Poland, Russia, Prussia and Wallachia – the geographical equivalent of the modern region that falls under the broad category of east-central Europe. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania also appears, for the first (known) time, on the 1491 copy of Sarmatia; yet its capital city is identified only as an unnamed cartographical spot. Clearly, the 1513 copy attempts to rectify the cartographic obscurity of Lithuania by sprinkling its territory with several named and well-marked towns. Ironically, the cartographers were so enthusiastic in populating Lithuania with numerous cities and castles that they recorded Vilnius twice on the same map.

The first record correctly identifies the Lithuanian capital as the town of Wilno by situating it at the confluence of two (unnamed) rivers. The second record incorrectly marks the city as Bilde located south of the original Wilno. The name Bilde, which has no known historical equivalent, appears to be a corrupt version of the place name Wilde, occasionally used to identify Vilnius in several German-language descriptions of Lithuania of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The German usage of Wilde as a name for Vilnius (as in die Statt Wilde, für die Wilde, zur Wilde) stems from fourteenth century chronicles of the Teutonic Order, a crusading monastic organization whose primary ideological and geopolitical prerogatives were the conquest and Christianization of pagan Lithuanians.9

|

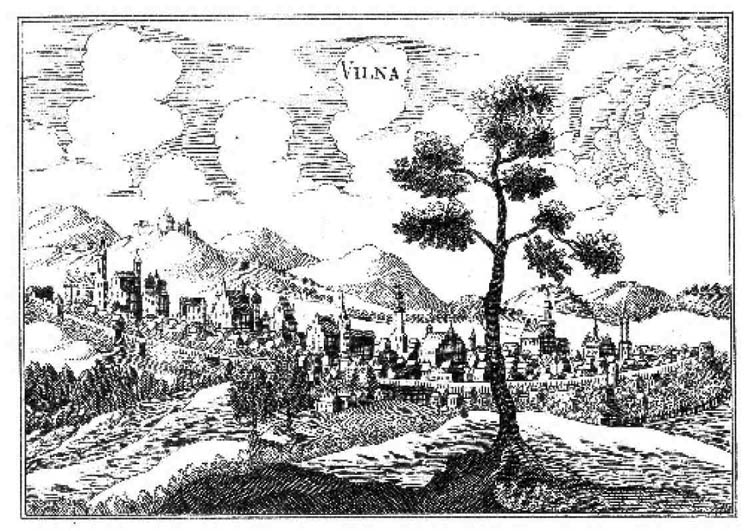

| View of Vilnius in the Early 17th century.

Lithograph by Ch. Barousse (19th c.) after T. Makowski. Copper engraving. |

Place name misnomers were not unusual in the earlier European chronicles (or for that matter in the colonial records of European empires), and in the frontier-like environment of Lithuania, vernacular names were subject to a great variety of misspellings and linguistic alterations. Yet the orthographic affinity of Wilde to Wilna (or Vilnius) probably has something to do with the ideological, and in this case, geo-religious struggle over control of Lithuania. The German word Wilde has very specific connotations: der/die Wilde means savage or wild. The vast forested territory which separated Vilnius from the Teutonic Knights’ possessions in Prussia was depopulated due to the endless raids of the crusaders and was simply referred to in German as die Wildnis – the wilderness. The crusaders called their regularized military expeditions into pagan Lithuania reysen, an adventurous excursion into a feral territory similar in spirit, if not tactics, to an aristocratic hunting party10

Throughout the fourteenth century, despite being concentrated on the eastern fringes of the Baltic Sea, the warfare between the Teutonic Knights and Lithuanians resonated all over Catholic Europe. The continuous crusades were ordered by the pope, and among the arriving crusaders there were:

Bohemians in 1323, Alsatians in 1324, Englishmen and Walloons in 1329, Austrians and Frenchmen in 1336. John of Bohemia made three trips, as did John Boucicaut and Count William IV of Holland, Henry of Lancaster went in 1352. Henry of Derby, the future King Henry IV of England, went in 1390 and 1392. In 1377 Duke Albert of Austria came with 2,000 knights for his ‘Tanz mit den Heiden’ (Dance with the Heathen). In the following year the duke of Lorraine joined the winter reysa with seventy knights. Shortly after this Albert of Austria turned up again with the Count of Cleves and they had a special reysa laid out for them so that they could fulfill their vows before Christmas. Count William I of Guelderland went seven times between 1383 and 1400.

The winter reysa was a chevauchée of between 200 and 2,000 men with the aim simply of devastating a given area as quickly as possible. There were usually two of these a year, one in December, the other in January or February, with a gap between the Christmas feast. The sommer-reysa was usually organized on a large scale with the intention of gaining territory by destroying an enemy strongpoint or building a Christian one, although plundering was a feature too. These reysen were not unlike sports, subject to the weather conditions in much the same way as horse-racing is today ... Were it not for the brutality and the very real hardships, one is tempted to write of the reysen as packaged crusading for the European nobility, and their popularity demonstrated how attractive this package could be when wrapped in the trappings of chivalry. But they depended on the existence of a frontier with paynim and an infidel enemy which could be portrayed as being aggressive.11

Vilnius, which was unsuccessfully stormed by the crusaders several times, entered the European geographical consciousness during this century of perpetual reysen.12

The medieval perception of the city was no doubt augmented by the factual religious beliefs and practices of local pagan people, who worshiped natural phenomena, such as the sun, the moon, thunder, animals, and especially, trees and the forest. According to numerous historical records and archaeological evidence, the most important pagan Lithuanian shrine was located at the historical heart of Vilnius – the confluence of the two rivers, Neris and Vilnia – and was protected by a sanctified oak grove. Since ancient Greek and Roman times, the Western European social and cultural comprehension of urban spatiality has always been associated with a clear symbolic and very often physical separation between the natural and the civic worlds. This eccentric toponym of Wilde “organically” positioned the city outside urban (Christian) Europe: it made it a defining element of the Lithuanian wilderness. It should not come as a great surprise that once the Lithuanian elite accepted Christianity in 1387, the second religious act after the actual baptism conducted by the Catholic missionaries was the formalized cutting down of the sacred forest.

The representational schism of Vilnius on the updated map of Sarmatia was most likely only a cartographic echo of the pagan past of the city; and soon, Bilde vanished from the Renaissance face of Europe. The name Wilde, however, lingered for another century or two within various Western European annals of Lithuania, and its corrupt forms could still be found in French geographical records up until the beginning of the seventeenth century. This sporadic usage of Wilde by various European commentators was usually an indication of the author’s geographical ignorance, because by the time of the Baroque period, at least among more knowledgeable mapmakers and chroniclers, usage of more accurate place name forms for the city were common. But the perception of Vilnius as an urban frontier of the Lithuanian (or European) wilderness survived, and even in the modern era, many people have still commented on the spatial intimacy between the town and surrounding nature.

For example, Jan Bułhak (1876-1950), the most celebrated photographic recorder of twentieth century Wilno, summarized the topographical layout of the city with a simple but pictorially accurate statement: “A deep hollow with two rivers and forty temples, almost all covered over by hills and flooded by a sea of greenery – this is a typical description of Wilno.”13 In a more experiential fashion, an American visiting the city in the late 1930s described a train arrival into the city as a journey deeper into the wilderness:

It seemed entirely in accord with our preconceived notions of Russian Poland that, awaking early in the morning and peering through the windows of our sleeping car, we should behold dense forest of pine, fir and hemlock stretching away from both sides of the railway track. The moving panorama was the exact counterpart of the picture we had so frequently seen of the lonely evergreen wilderness of Poland and Russia, save for the absence of the inevitable sleigh stalked by famished wolves.14

Even a plane landing in contemporary Vilnius evokes among some of its more recent visitors a sense of being plunged into the realm of natural isolation. “The further east the plane flew,” notes a South African passenger, Dan Jacobson, who visited the city in the 1990s,

the less demarcated the landscape became, the fewer were the roads crossing it, the more rarely were vehicles to be seen. Ploughed fields turned into pasture lands, pastures into woods, woods into water, water into tussocky heaths and marshes. Each change was marked by a simple, limited change of color. No one appeared to be moving in the villages randomly dotted about. There were no mountains; hardly any hills ... The place looked almost as empty after we landed as it had from above.”15

If in post-Renaissance Europe, the name Wilde gradually faded from continental charts, then the name Sarmatia gained in strength as a mythopoetic equivalent of the Polish-Lithuanian geographical body. Indeed, the Baroque era imagination substantiated Sarmatia with a remarkable sense of cultural, political and social reality. In this sense, Sarmatia was foremost a province of Baroque mannerism, a spatial paradox suspended somewhere between narrative illusion and geographical reality.

The cartographic origins of Sarmatia could be traced back to the geographical and historical works of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Reputedly, Ptolemy situated the barbarian tribe of the Sarmatians somewhere in the steppes between the Azov and the Caspian Sea. Herodotus and other commentators moved the semi-nomadic Sarmatians westwards to the area of the Black Sea and the lower basin of the Dnieper River. Some time later, this tribe of permanent wanderers was moved further north to the region where the vast southern steppes and plains of Eurasia meet the northern forest and marshlands of the Baltic Sea littoral. According to Tacitus, this was an unexplored land somewhere near the “Suabian Sea” (most likely, the Baltic Sea) where “our knowledge of the world ends.”16 Centuries later, some time in the early part of the fifteenth century, this barely mapped-out land of the southeastern coast of the Baltic Sea was resurrected as Sarmatia terra in Europe. The sea itself acquired a Sarmatian identity and was often identified on the maps of Europe as Mare Sarmaticum.

Undoubtedly, the historical reputation of the region as the area inhabited by some of the last pagan peoples in Europe strengthened the mapmaker’s case for locating the land of ancient, barbaric Sarmatians along the Baltic Sea coastline. By the mid-sixteenth century, the Renaissance desire to bring geographical and ethnographical information found in ancient texts and maps into the contemporary spatial purview of Europe put Sarmatia into a cartographic limbo. The region had already been divided into several countries, such as Prussia, Lithuania (and Samogitia), Livonia and Poland, and there simply was no space for the ancient Sarmatians to dwell in between these clearly demarcated political entities. As compensation for this political impasse, the Sarmatian cartographic image was stretched farther so it could accommodate its historical and contemporary elements. This made Sarmatia an extremely elastic and elusive entity, with a variable geographical shape and constantly shifting boundaries. In the end, Sarmatia’s exact geographical location was never reliably mapped out. Not unlike its tribal forefathers, who roamed between the known and unknown realms of the ancient world, “modern” Sarmatia was a nomadic entity.

Indeed, on many maps of the Baroque period, Sarmatia was the only European country that had its geographical doppelgänger in Asia, Sarmatia Asiatica. The European part of Sarmatia was controlled by Christian rulers – the Asian side dominated by Muslims. (In this sense, Sarmatia was an early cartographical embodiment of the modern idea of Eurasia.) Moreover, since not every map of Europe even carried the name of Sarmatia, the dissected land of the Sarmatians acquired a phantom existence. The country and its people periodically appeared on the maps of Europe only to vanish again.

This ethereal existence of Sarmatia was made more corporeal by the emergence of Sarmatism, a peculiar sociocultural milieu that found a fertile ground among the Polish-Lithuanian nobility of the sixteenth century. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was one of the largest countries in Europe, stretching at the time from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Its nobility, like most elite societies of Europe, enjoyed an elaborate Renaissance sense of spectacle. Local theatrical rituals “exhibited typical Polish traits despite being founded on a common European practice which derived from ancient Greek and Roman tradition, later enriched by Roman Catholic liturgy and the ceremonies displayed in the courts of feudal monarchs throughout medieval Europe, as well as by some Oriental influences.”17 It was through such lavish representational fusions that Sarmatia passed from the cartographic Theatrum of the Renaissance mind into the sociopolitical stage of the Baroque age.

Sarmatism resulted from a fusion of regional patriotism with the rediscovery of classical Greek and Roman maps and texts. Although Sarmatism was based on ancient geo-mythology, it “was a unique variation of what might be called Renaissance national self-definition. In the Renaissance spirit of a return to sources, the peoples of Europe searched for or created their own (mythic) origins. Sarmatism expressed for the Poles the idea that, like other European nations, they too had their origins in the peoples discussed by the authors of antiquity, but their ancestors were even older than some of those claimed by many other Europeans.”18 And if the Renaissance turned Sarmatism into a political (national) ideology, then Baroque made it a cultural (social) phenomenon.

Baroque emerged in Rome, but within a few decades, this new artistic style captured most of Europe. In the northcentral parts of Europe, the dispersion of Baroque sensualities followed the jagged military movements of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), which, by pushing massive armies endlessly across national frontiers, contributed to the decimation of the region.19 In Poland-Lithuania, this war was followed by what later historians called the Deluge (1648-1667), a cycle of massive foreign invasions, from the Swedes to the Ukrainian Cossacks and from the Ottomans to the Muscovites. The Commonwealth never truly recovered from this upswing of war and mass death. Under such circumstances, the cultural orientation of the Baroque towards the center of the Catholic world – Rome – proved to be quite popular in Poland-Lithuania, which, since the fall of Constantinople in the fifteenth century, had acquired the title of the antermurale christianitatis, the bulwark of Christendom.

By the middle of the seventeenth century, the Commonwealth was already a ruined fortress. It could never defend its own borders, not to mention the imaginary or geopolitically constructed boundaries of Europe. Out of this military inability came a mythological orientation of Sarmatism that reached its sociocultural heights at the end of the seventeenth century. More precisely, the apogee of Sarmatism corresponded with the glorious delivery of Vienna from the Turkish siege by the Polish- Lithuanian forces in 1683. For the Commonwealth, the political spoils of victory were short-lived, because the country’s prestige in Europe had already been significantly damaged by a series of military defeats and debilitating social, economic and natural disasters. Paradoxically, after one of the most significant victories in the centuries-long struggle of the European Christian states with the Ottomans, having “lost all hope of salvation, Polish society turned in on itself and, bewitched by the imaginary ideals of ‘Old Sarmatia’, began to lose sight of elementary realities.”20 By the beginning of the eighteenth century, during the so-called Saxon era (1697-1764), when the Commonwealth was ruled by two foreign monarchs (the electors of Saxony), Sarmatism acquired its explicit qualities of nostalgic inwardness and sentimental isolationism.

The surprising result of this self-imposed and imagined Sarmatian seclusion – after all, the country continued to be occupied and plundered by various foreign (Swedish, Russian, Saxon, etc.) armies – was the creation of a cultural and architectural opulence unmatched in the history of the Commonwealth. The Baroque synthesis of splendor and ruin, best exemplified in the celebratory and/or rhetorical elaborations of funerary processions and architecture, provided the most impressionable answer to the seemingly senseless succession of plundering armies. Amidst this commonplace routine of victories and defeats, liberations and conquests, and life and death, the perceptual distance between beauty and decay was erased. Numerous foreign glories brought national catastrophes to Lithuania, but the military destruction of the country was often followed by the impulsive rebuilding of its urban relics. The transitory moments of life were celebrated through a topographical profusion of Baroque aesthetic splendor. Thus, while the local “economy stagnated” and “towns shrank […] the opera and theater flourished. The parks, the architecture, and the music were superb. All the arts found ample patronage.” 21 Naturally, churches were the first to be rebuilt, since they could serve both as monumental tokens of thanksgiving and elaborate spaces for holding the crypts and tombs of the elite.

Below the aristocratic cosmopolitan affluence and geopolitical indifference, there were some attempts to reconcile the ruinous state of the country with the notorious provincial traditionalism of the local nobility. As a result, “Polish Sarmatism, the characteristic style of the Saxon era, wallowed in the sentimentality of the Republic’s alleged glories and achievements, and is generally thought to have little literary or artistic merit. Allied to the fashion for oriental dress and decoration, it reinforced the conservative tendencies of the Szlachta [the nobility] and the belief in the superiority of their “Golden Freedom” and their noble culture.”22 By the time of enlightenment absolutism – the middle of the eighteenth century – Sarmatism turned into a twofold structure. On the surface, it displayed eccentric features of crafty Rococo splendor and vitality, but underneath this visual grandeur, there was a melancholic awareness of inevitable loss and decay.

Looking back from the contemporary perspective of the cultural and/or political irrelevance of Sarmatism, it is easy to forget that this semi-mythical milieu was an expression of a very strong national identity united through clearly defined social bonds and territorial loyalties. Sarmatia, despite its fluid historical and vaporous geographical nature, was not a vacuous space. It was filled with an unfolding array of people, objects and gestures that visibly demarcated its cultural and even political dimensions. Although the original Sarmatians, like the Goths, Vandals and Huns, had left the space of Europe a long time ago, their blood and heritage were thought to have created a distinct social-cultural milieu of the Polish szlachta. In this sense, the Polish and Lithuanian nobilities often envisioned Sarmatia as a palimpsest with endless genealogical inscriptions and family ties. The porous borders of the Commonwealth played an important role in shaping the peculiarities of the Sarmatian culture. And while many “practices stemmed from the expressiveness of the pan-European Baroque ... they developed unique forms in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in part because of its extensive contact with Russian and Ottoman civilization.” 23 Various daily rituals, official ceremonies, habitual gestures, oratorical diatribes and of course language, kept the Sarmatian nation of the Polish-Lithuanian nobility apart from other surrounding nations, such as Saxons, Prussians, Swedes and Russians. The Polish szlachta wore specific Sarmatian garments, followed unique Sarmatian social and religious practices, and even suffered from a bizarre local medical pathology, explicitly identified in Latin as plica Polonica.24

The fictionalized image of Sarmatia was supported by the theatricality of Baroque imagination, which freely mixed ancient epics, biblical scenes, exotic locations, fantastic motifs and contemporary European political events into an unfolding spatial drama. Still, Sarmatism was a modern phenomenon, for its national distinctiveness relied heavily on the imagined coherence of a diverse ethno-social community. Nobles comprised about 10 percent of the total population of Poland-Lithuania – it was probably the largest and most privileged noble class in Europe. (In most western European countries, the nobility consisted of fewer than 5 percent of the population.) On the other hand, the nobility of the Commonwealth was neither culturally, linguistically and/or economically homogenous: it comprised families of Polish, Lithuanian, Ruthenian, Russian, Tartar, German and some other foreign origins. It also included adherents of the Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, Uniate and even Muslim religions. Among the nobles, there were people of various financial means, from exceptionally wealthy magnates to the extremely poor landless szlachta. Despite these differences, the noble families were all united under a public spectrum of political equality and social brotherhood. Sarmatism not only framed this diverse body through specific political practices, but also served as a culturally connecting thread. The everyday practice of Sarmatism celebrated and empowered the local nobility, which understood its social and geopolitical role as a messianic duty to protect its own rights and privileges. The Polish-Lithuanian nobles were absolutely convinced that they lived in the best society in the world and attributed this achievement to the Sarmatian origins of their Commonwealth. It was also widely believed that Sarmatia reached its golden age in the sixteenth century, at the time of the Lublin Union, which in 1569 created the confederate republic of Polish and Lithuanian nobilities. Hence, in many ways, the nobility’s conservatism and “resistance to reform came from love of liberty and xenophobia.”25

Despite this apparent inner coherence, in the eyes of European commentators Sarmatism remained a cultural oddity. The most bewildering aspect of Sarmatism was its temporal disharmony, for Sarmatia appeared as both a contemporary and ancient space, a land of indecisive (historical) erasures and imprecise (contemporary) inscriptions. Furthermore, while it was widely acknowledged that Sarmatia implied a spatial and cultural frontier, it was not clear what lands, or whose territories and histories it (dis)connected. In short, for enlightened western Europeans, Sarmatia appeared not so much as a geographical palimpsest, but as a farcical theatre. In 1784, the French count de Segur, for instance, described the road from Berlin to Warsaw as an ethnographical journey in time where “everything makes one think one has been moved back ten centuries, and that one finds oneself amid hordes of Huns, Scythians, Veneti, Slavs, and Sarmatians.”26 The count experienced Warsaw as a place located “at the extremity of the world,” where a passing observer was greeted with a “sort of palace of which one half shined with noble elegance while the other was only a mass of debris and ruins, the sad remains of a fire.”27 On the southern edges of the expanding Russian empire, somewhere in the region of the lower Dnieper River – the assumed original homeland of the ancient Sarmatians – Segur, on his way from Saint Petersburg to the Crimea (just recently won by the tsarina from the Ottomans) again encountered a parade of centuries and peoples. “It was,” recalled the count “like a magic theatre where there seemed to be combined and confused antiquity and modern times, civilization and barbarism, finally the most piquant contrast of the most diverse and contrary manners, figures, and costumes.”28

Within this vast array of centuries and peoples, it was easy for most foreigners to overlook the geographical and ethnological peculiarities of Lithuania. In general, foreign knowledge of Lithuania was scant and sketchy at best. Few people, except for the invading armies whose knowledge of the country was too transitory and predatory, visited the country. Up until the eighteenth century, many printed cosmographies of Europe still claimed Lithuania to be a country of impenetrable woods and endless swamps, inhabited by uncivilized people living in close proximity with wild beasts. Occasionally, reports from more knowledgeable visitors tried to prove otherwise by stating that while the country was extensively covered by woods, its natural world was full of exceptional wonders. In their opinion, the landscape was pleasant enough, and the forest rich in exotic animals and plants that had become extinct in more urbane parts of the continent. And although there were few cities and towns, there was plenty of good and cheap food to support the country’s largely rural population.

Most visitors, however, agreed on one point: travelling in Lithuania required time, patience, and good health, because bumpy roads, swampy terrain, icy rivulets, unpredictable climate, uncultivated wilderness, desolate countryside, and a lack of most travel comforts made a trip a strenuous experience. Vilnius in particular was difficult to reach. In short spells of dry weather, mostly in summer, coaches could barely pass through narrow dusty highways; in most other times, soggy sandy roads bogged down any movement. Some travellers suggested making a more comfortable trip in a sleigh during long winter months. In addition, locals could offer only simple food and shelter of extremely poor quality, for the area around the Lithuanian capital was one of the poorest regions in the entire country. Still, several visitors noted a genuine hospitality offered by the wealthy magnates of the country which, at least, for a privileged few, made visiting Vilnius an enjoyable social pleasure.

Very often foreign accounts compared Lithuania to Poland, finding Lithuanian society much more lax in social discipline, cultural sophistication and sexual morals than its more westernized counterpart. The (noble) Lithuanians were periodically described as sluggish drunkards who enjoyed neverending hunting and opulent dinner parties. Some travellers also reported an unusually high degree of tolerance regarding the accepted norms in gender relations and sexual practices. The wives and daughters of the Lithuanian noble families were described as being as interested in sex as their husbands and fathers. According to some occasional reports, many unmarried women in Lithuania were allowed to freely engage in sexual activities, and even after their marriage, they were permitted to keep lovers with the consent of their husbands. So if the Lithuanian males were often depicted as louts engaging visitors with their unsophisticated bravado, then local women were portrayed as sirens seducing travellers by their highly cultivated amorousness.

Satirical poems and anecdotal jokes about lewd Lithuanian women were very common among the Poles, who had a much closer and more intimate relationship with the Lithuanians than any other people of Europe. Early printed accounts describing the Lithuanian practice of matrimoniae adiutores appeared in Polish and German manuscripts of the late medieval period, and, in later centuries, they regularly surfaced within various Western European chronicles. An English version of such an account was reprinted in 1611 in the cosmographic text written by J. Boemus in Latin, a few decades earlier. This geographical book, entitled The manners, lawes and customs of all nations, states that Lithuanian women “have their chamber-mates & friends by their husband permission, & those they call helpers or furtherers of matrimony, but for a husband to commit adultery is held disgraceful and abominable: Marriages there be very easily dissoluted, by consent of both parties, and they marry as oft as they please.”29 It is hard to know how accurate the descriptions of Lithuanian sexuality were, since most cosmographies of the Baroque era meant to entice readers with scandalous stories of barbarous lust and exotic gender characteristics. It is also not known whether foreign visitors based their reports of the sexual practices of Lithuanian women on their personal experience or on gossip gathered while travelling through the country. However, one thing is clear, by the standards of the time, Lithuanian (noble) women had many more social and economic rights than their western European counterparts, officially enshrined in the legal code of dukedom, the Lithuanian Statute. This fact alone might suffuse the unverifiable statements concerning the sexual practices of Lithuanian society with a certain degree of cultural legitimacy.30

(To be continued)

Continued in our Vol 54:1, Spring 2008 issue

1. Wilson and Dusten, 1993.

2. Hale, 1994, 38.

3. Ibid., 20.

4. Ibid.

5. On the early history of the cartography of Lithuania, see

Vaitekūnas,

1997; also Maksimaitienė, 1991.

6. Hale, 1994, 24.

7. Ibid.

8. Gudienė, 1999.

9. On historical variations of the name Vilnius, see

Jurkštas, 1985; Toporov,

2000; Vanagas, 1993.

10. On the Teutonic Order, see the works of Urban, 1975, 1989, 2003.

11. Riley-Smith, 2005, 253.

12. Chaucer captured the European scope of the crusader’s

reysa

against pagan Lithuanians in the passage of Canterbury Tales

depicting

the adventures of the Knight, who: “Full often time he had

abroad bygone / Above all nations, to Prussia. / In Lithuania had he

reysed and in Russia / No Christian man of his degree more

often.”

Roy, 1999, 69

13. Markevičienė, 1999, 104.

14. McBride, 1983, 111-112.

15. Jacobson, 1999, 109.

16. Davies, 1982, 45.

17. Bogucka, 1996, 36.

18. Kaufmann, 1995, 288.

19. Munck, 1990, 81-108.

20. Davies, 1982, 367.

21. Ibid., 508.

22. Davies, 2001, 265.

23. Stone, 2001, 211-213.

24. For more information on the Sarmatian style, see

Matuškaitė, 2003,

95-222; Martinaitienė, 2001, 165-175.

25. Stone, 2001, 211-212.

26. Ségur, quoted in Wolff, 1994, 19.

27. Ibid., 20.

28. Ibid., 130.

29. Joannes, 1611, 221-222.

30. For more on the foreigners’ views on Lithuania see

Kamutavičius,

2002.

42

WORKS CITED

Bogucka, Maria. The Lost World of the ‘Sarmatians.’ Warszawa: Polish Academy of Science, Institute of History, 1996.

Davies, Norman. God’s Playground: A Hostory of Poland, vol. 1. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Gudienė, Danguolė, ed. Lithuania on the Map. Vilnius: Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus, 1999.

Hale, John. The Civilization of Europe in the Renaissance. New York: Atheneum, 1994.

Jacobson, Dan. Heshel’s Kingdom. London: Penguin Books, 1999.

Jonnes, Boemus. The manners, lawes and customs of all nations with many other things.... London: 1611.

Jovaiša, Liudas and Tumelis J., eds. Visitatio dioceses Samogitiae (A. D. 1579)/ Žemaičių vyskupijos vizitacija. Vilnius: Mokslas, 1998.

Jurkštas, Jonas. Vilniaus vietovardžiai. Vilnius: Mokslas, 1985.

Kamutavičius, Rustis. “Lietuvos įvaizdžio stereotipai italų ir prancūzų XVI-XVII a. literatūroje.” Ph.D dissertation. Kaunas: Vytauto Didžiojo Universitetas, 2002.

Kaufmann, Thomas Da Costa. Court, Cloister and City: The Art and Culture of Central Europe, 1450-1800. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

McBride, Robert Mediil. Towns and Peoples of Modern Poland. New York: McBride and Company, 1938.

Maksimaitienė, Ona. Lietuvos istorinės geografijos and kartografijos bruožai. Vilnius: Mokslas, 1991.

Markevičienė, Jūratė. “Genius Loci of Vilnius.” Vilnius: Lithuanian Literature, Culture, History, Summer 1999.

Martinaitienė, Gražina Marija. “At the Crossings of Western and Eastern Cultures: the Contush Sashes.” Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės barokas: formos, įtakos, kryptys, Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis 21, 2001.

Matušakaitė, Marija. Apranga XVI-XVIII a. Lietuvoje. Vilnius: Aidai, 2003. 43

Miłosz, Czesław. “Looking for a Center: On the Poetry of Central Europe.” Beginning with My Streets: Essays and Recollections. Translated by Madeline G. Levine. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1991.

Munck, Thomas. Seventeenth Century Europe: 1598-1700. London: Macmillan, 1990. Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The Crusades: A History. New Haven, Yale University Press, 2005.

Roy, James Charles. The Vanished Kingdom: Travels Through the History of Prussia. Boulder: Westview Press, 1999.

Stone, Daniel. The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386-1795. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001.

Titunik, I. R. “Baroque,” Handbook of Russian Literature, Victor Terras, ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

Toporov, Vladimir. “Vilnius, Wilno, Vil’na: miestas ir mitas, Baltų mitologijos ir ritualo tyrimai.” Vilnius: Aidai, 2000.

Urban, William. The Baltic Crusade. Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1975.

_____. The Samogitian Crusade. Chicago: Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, 1989.

_____.The Teutonic Knights: A Military History. London: Greenhill, 2003.

Vaitekūnas, Stasys. “Lietuviškosios kartografijos istorijos bruožai,” Lietuvos sienų raida, vol 2., Algimantas Liekis, ed. Vilnius: Lietuvos mokslas, 1997.

Vanagas, Aleksandras. “Miesto vardas Vilnius,” Gimtasis Žodis, Nr. 11(59), Novembr, 1993.

Wilson, Kevin and Jan van der Dusten, eds. The History of the Idea of Europe. London: Routledge, 1993.

Wolff, Larry. Inventing Eastern Europe: the Map of Civilization on the Mind of the Enlightenment. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994.